Business Case

“Good jobs.” “Sustainability.” “Healthy work.”

They’re all ideas in a growing movement about the value of good quality jobs. It recognizes that employee safety, health and well-being are key components of sustainability. Healthy work encourages management strategies and organizational changes that improve the quality of work, and are good for business, workers and society. Unhealthy work, on the other hand, has a substantial impact on the cost of doing business.

Want to know the business costs of unhealthy work? Click here.

How do we know? Read on.

The rapidly changing nature of work, the employment relationship, and a fiercely competitive global economy continue to pressure employers to utilize business models that are intended to maximize productivity and profitability but ultimately conflict with healthy, good jobs. Restructuring, downsizing, sub-contracting, and lean production are common strategies used by many organizations in high-income industrialized countries, including the U.S. These practices rely on increasing short-term efficiency and cutting labor costs, often resulting in understaffing, intensifying the pace of work, more temporary or insecure jobs, and longer hours.[1],[2]

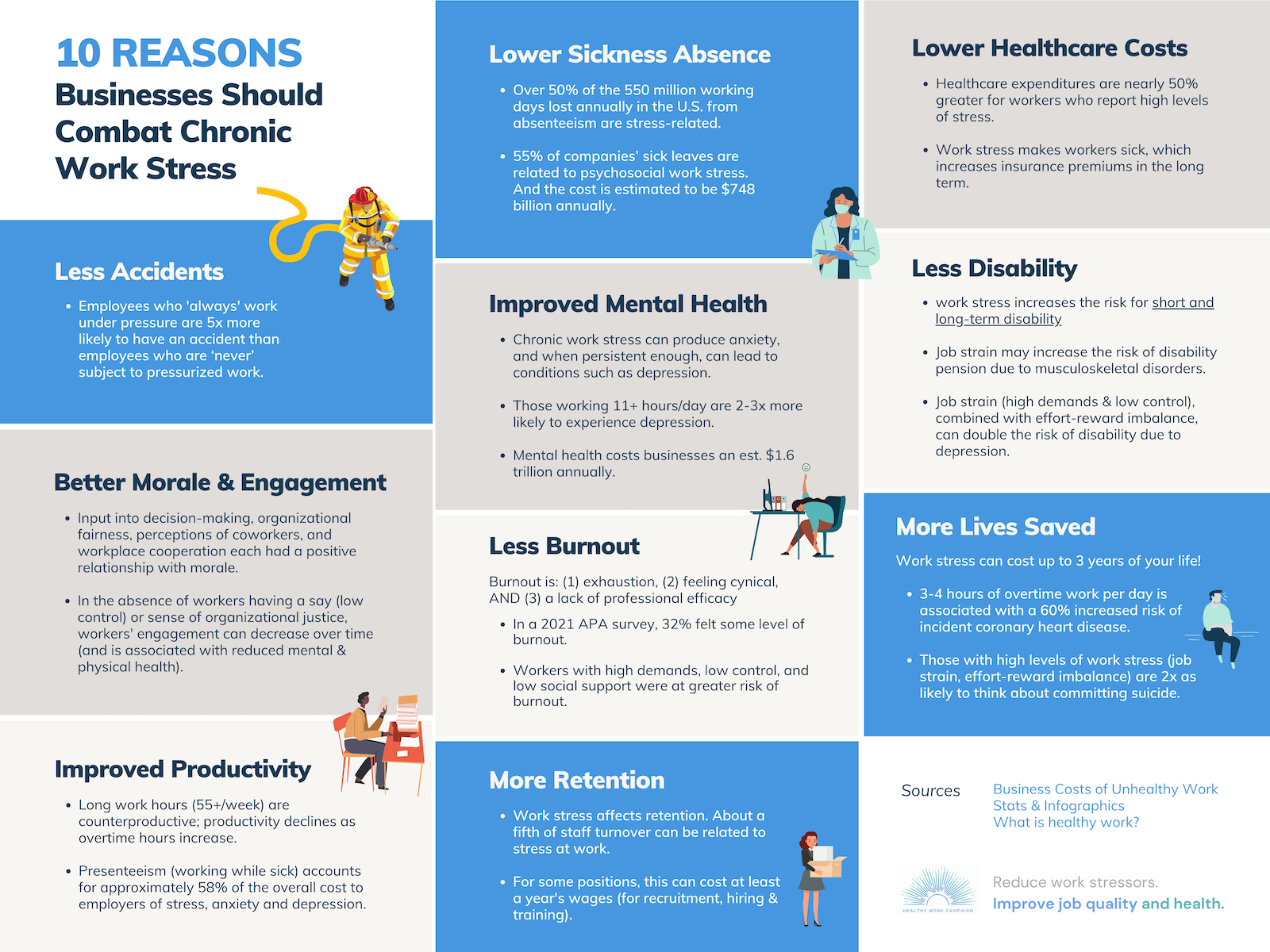

Long work hours turn out to be counterproductive; productivity declines as overtime hours increase.[3],[4] And other practices can result in “psychosocial work stressors” (e.g., excessive demands, low control, work-family conflict), which are scientifically measurable occupational hazards that result in an increase in experienced stress and mental distress.[5] Work stressors are an indicator of “unhealthy work” and have a negative effect on employee engagement,[6] health, and well-being.

A large body of research shows that employees chronically exposed to work stressors have an increased likelihood of injuries on the job,[7],[8] as well as developing mental health conditions such as anxiety and burnout,[9] and when persistent enough, can lead to conditions such as depression,[10] hypertension[11],[12] and cardiovascular disease.[13],[14] (See Principles of Healthy Work and Stats to Know for more info.)

So what are the costs?

- Overall costs

The direct and indirect costs of work-related stress to companies is estimated in the hundreds of billions[15], including:

- increased healthcare premiums

- increased costs from increased absenteeism/sick leave, disability management

- diminished productivity at work [presenteeism]

- employee turnover

- Significant increases in healthcare costs, because unhealthy work can make your workforce sick and more likely to experience health problems which can be persistent, difficult to treat, and expensive.

See Stats

-

- Healthcare expenditures are nearly 50% greater for workers who report high levels of stress. (Goetzel et al. J Occup Environ Med, 1998)

- Workplace stressors associated with how U.S. companies manage their workforces are conservatively estimated to incur healthcare costs in excess of $180 billion, approximately 5-8 percent of total annual healthcare costs. (Goh, Pfeffer, Zenios, Management Science, 2015)

- Significant losses in productivity due to sickness absenteeism, presenteeism, and turnover, as well as increased costs of disability programs including workers compensation insurance:

See Stats

- Sick leave/AbsenteeismThe number of days employees reported not being able to do their work and usual activities due to illness.

Over half of the 550 million working days lost annually in the U.S. from absenteeism are stress related and one in five of all last minute no-shows are due to job stress. (European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA), Calculating the cost of work-related stress and psychosocial risks, 2014)

In the United Kingdom, in 2015/16, over 11 million days are lost at work a year because of stress at work and 24 working days are lost per person. (UK Health and Safety Executive, Health and Safety at Work: Stress, anxiety and depression statistics, 2015/16)

Stress accounts for about 40% of sickness absence, at an estimated average cost of £175 (U.S.$ 228) per employee/year. (Hoel, H., Sparks, K. and Cooper, C.L., International Labour Organization (ILO), Geneva, 2001)

- PresenteeismEmployees report being at work but not performing to their usual capacity due to illness.

Presenteeism accounts for approximately 58% (32% is due to absenteeism) of the overall cost to British employers of stress, anxiety and depression. Therefore, presenteeism costs a company with 10 employees an estimated £6 050 per year. (Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, Mental health at work: developing a business case policy paper, 2007)

With higher levels of reported job stress (including understaffing because of absences/vacancies, having ‘‘too many’’ clients, time pressure, and “too much work’’), sickness presenteeism occurred more often than sickness absence among elder care workers. (Elstad, Scan J Pub Health, 2008)

- DisabilityThe inability to work or engage in one's accustomed role because of a medically definable impairment, results in costs to employers of disability benefits programs or disability management, the loss of productivity due to disability or replacing workers on disability leave.

In a study of over 40,000 employees followed over time, the combination of job strain and ERI was associated with doubling the risk of disability due to depression. (Juvani et al, SJWEH, 2018)

A higher job strain score was associated with a 1.3-2.4 times higher risk of disability pension due to musculoskeletal disorders four and half years later. (Mantyniemi et al, Occup Environ Med, 2012)

- Workers CompensationCost of private or state insurance that provide wage replacement and medical benefits to employees experiencing a work-related injury or work-related illness (such as a heart attack) while on the job; cost of replacing workers injured on the job.

Among employees who state that they ‘always work under pressure’, the accident rate is about five times higher than that of employees who are ‘never’ subject to pressurised work. (European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Work-related stress, 2007)

High psychological demands, emotional demands, and conflicts with supervisors and coworkers increased the risk of being injured in an occupational accident even taking into account demographics, fatigue, shift work and type of work environment. (Swaen et al, J Occup Environ Med, 2004)

- Staff TurnoverThe cost of replacing an employee who is terminated or voluntarily leaves and includes recruitment, hiring, and training costs.

National studies show that about a fifth of staff turnover can be related to stress at work. (CIPD Recruitment, retention and turnover, 2008 in European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA), Calculating the cost of work-related stress and psychosocial risks, 2014)

The cost of voluntary white-collar turnover is estimated to be at least a year’s compensation for the position. (Ramlall, S., Journal of the American Academy of Business, 2004)

- Sick leave/AbsenteeismThe number of days employees reported not being able to do their work and usual activities due to illness.

Next steps

Taken all together, these various costs from work stressors are a significant economic burden for organizations and can be barriers to creating greater innovation, engagement, and ultimately healthy and sustainable organizations.

There are also the human costs of work stress to families, children and communities to be considered, as well as the societal effects of increased disability, morbidity and mortality.

Attention to #healthywork is an imperative for those organizations committed to sustainability and providing good jobs to a motivated and engaged workforce. Fortunately there are many resources and tools available to help guide your organization or business.

- Check out the Healthy Work Survey on our Healthy Work Assessments page to identify work stressors in your workplace.

- Check out Solutions for Employers to find resources, guidance, and examples of ways to reduce work stressors and improve health and well-being.

Need tailored guidance?

Book a consultation with us here.

References

[1] Landsbergis, P. A., et al. (1999). “The impact of lean production and related new systems of work organization on worker health.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 4(2): 108-130.

[2] Virtanen, M., et al. (2005). “Temporary employment and health: a review.” Int J Epidemiol 34(3): 610-622.

[3] Caruso, C. C. (2006). “Possible broad impacts of long work hours.” Ind Health 44(4): 531-536.

[4] Pencavel, J. (2014). “The Productivity of Working Hours.” The Economic Journal 125(589).

[5] Schnall, P., et al. (2009). Unhealthy Work: Causes, Consequences and Cures. Amityville, NY, Baywood Publishing.

[6] Schaufeli and Bakker. (2004) “Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study.” J Organiz Behav 25; 293-315.

[7] Dembe AE, et al. (2005) “The impact of overtime and long work hours on occupational injuries and illnesses: new evidence from the United States.” Occup Environ Med; 62(9): 588-597.

[8] Swaen GM, et al. (2004) “Psychosocial work characteristics as risk factors for being injured in an occupational accident.” J Occup Environ Med; 46(6):521-7.

[9] Aronsson, G., et al. (2017). “A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms.” BMC Public Health 17: 264.

[10] Theorell, T. and G. Aronsson (2015). “A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms.” BMC Public Health 15: 738.

[11] Gilbert-Ouimet, M., et al. (2014). “Adverse effects of psychosocial work factors on blood pressure: systematic review of studies on demand-control-support and effort-reward imbalance models.” Scand J Work Environ Health 40(2): 109-132.

[12] Landsbergis, P., et al. (2013). “Job strain and ambulatory blood pressure: A meta-analysis and systematic review.” American Journal of Public Health 103(3): e61-e71.

[13] Schnall, P. L., et al. (2016). “Globalization, Work, and Cardiovascular Disease.” International Journal of Health Services 46(4): 656-692.

[14] Theorell, T., et al. (2016). “A systematic review of studies in the contributions of the work environment to ischaemic heart disease development.” The European Journal of Public Health 26(3): 470-477.

[15] Theorell, T., et al. (2016). Jauregui and Schnall (2009). “Work, Psychosocial Stressors and the Bottom Line.” Unhealthy Work: Causes, Consequences, Cures. Amityville, NY, Baywood Publishing.